Rutherford scattering

In physics, Rutherford scattering is a phenomenon that was explained by Ernest Rutherford in 1911,[1] and led to the development of the Rutherford model (planetary model) of the atom, and eventually to the Bohr model. It is now exploited by the materials analytical technique Rutherford backscattering. Rutherford scattering is also sometimes referred to as Coulomb scattering because it relies only upon static electric (Coulomb) forces, and the minimal distance between particles is set only by this potential. The classical Rutherford scattering of alpha particles against gold nuclei is an example of "elastic scattering" because the energy and velocity of the outgoing scattered particle is the same as that with which it began.

Rutherford also later analyzed inelastic scattering when he projected alpha particles against hydrogen nuclei (protons), and this latter process is not classical Rutherford scattering, although it was first observed by him. At the end of such processes, non-coulombic forces come into play. These forces, and also energy gained from the scattering particle by the lighter target, change the scattering results in fundamental ways which suggest structural information about the target. A similar process probed the insides of nuclei in the 1960s, and is called deep inelastic scattering.

The initial discovery was made by Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden in 1909 when they performed the gold foil experiment under the direction of Rutherford, in which they fired a beam of alpha particles (helium nuclei) at layers of gold leaf only a few atoms thick. At the time of the experiment, the atom was thought to be analogous to a plum pudding (as proposed by J.J. Thomson), with the negative charges (the plums) found throughout a positive sphere (the pudding). If the plum-pudding model were correct, the positive “pudding”, being more spread out than in the current model of a concentrated nucleus, would not be able to exert such large coulombic forces, and the alpha particles should only be deflected by small angles as they pass through.

However, the intriguing results showed that around 1 in 8000 alpha particles were deflected by very large angles (over 90°), while the rest passed straight through with little or no deflection. From this, Rutherford concluded that the majority of the mass was concentrated in a minute, positively charged region (the nucleus) surrounded by electrons. When a (positive) alpha particle approached sufficiently close to the nucleus, it was repelled strongly enough to rebound at high angles. The small size of the nucleus explained the small number of alpha particles that were repelled in this way. Rutherford showed, using the method below, that the size of the nucleus was less than about 10−14 m (how much less than this size, Rutherford could not tell from this experiment alone; see more below on this problem of lowest possible size).

Contents |

Derivation

The differential cross section can be derived from the equations of motion for a particle interacting with a central potential. In general, the equations of motion describing two particles interacting under a central force can be decoupled into the motion of the center of mass and the motion of the particles relative to one another. For the case of light alpha particles scattering off heavy nuclei, as in the experiment performed by Rutherford, the reduced mass is essentially the mass of the alpha particle and the nucleus off of which it scatters is essentially stationary in the lab frame.

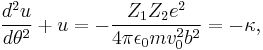

Substituting into the Binet equation yields the equation of trajectory

where  ,

,  is the speed at infinity, and

is the speed at infinity, and  is the impact parameter.

is the impact parameter.

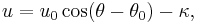

The general solution of the above differential equation is

and the boundary condition is

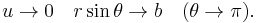

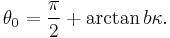

Then we can find that

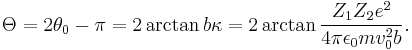

The deflection angle Θ can be seen from the graph or solving  as

as

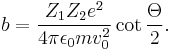

b can be solved readily

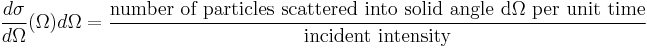

To find the scattering cross section from this result consider its definition

Since the scattering angle is uniquely determined for a given  and

and  , the number of particles scattered into an angle between

, the number of particles scattered into an angle between  and

and  must be the same as the number of particles with associated impact parameters between

must be the same as the number of particles with associated impact parameters between  and

and  . For an incident intensity

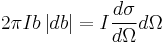

. For an incident intensity  , this implies the following equality

, this implies the following equality

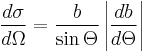

For a radially symmetric scattering potential, as in the case of the Coulombic potential,  , yielding the expression for the scattering cross section

, yielding the expression for the scattering cross section

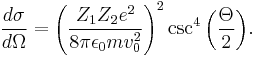

Finally, plugging in the previously derived expression for the impact parameter  we find the Rutherford scattering cross section

we find the Rutherford scattering cross section

Details of calculating maximal nuclear size

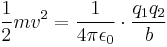

For head on collisions between alpha particles and the nucleus, all the kinetic energy of the alpha particle is turned into potential energy and the particle is at rest. The distance from the centre of the alpha particle to the centre of the nucleus (b) at this point is a maximum value for the radius, if it is evident from the experiment that the particles have not hit the nucleus.

Applying the inverse-square law between the charges on the electron and nucleus, one can write:

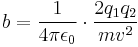

Rearranging:

For an alpha particle:

- m (mass) = 6.7×10−27 kg

- q1 = 2×(1.6×10−19) C

- q2 (for gold) = 79×(1.6×10−19) C

- v (initial velocity) = 2×107 m/s

Substituting these in gives the value of about 2.7×10−14 m. (The true radius is about 7.3×10−15 m.) The true radius of the nucleus is not recovered in these experiments because the alphas do not have enough energy to penetrate to more than 27 fm of the nuclear center, as noted, when the actual radius of gold is 7.3 fm. Rutherford realized this, and also realized that actual impact of the alphas on gold causing any force-deviation from that of the 1/r coulomb potential would change the form of his scattering curve at high scattering angles (the smallest impact parameters) from a hyperbola to something else. This was not seen, indicating that the gold had not been "hit" so that Rutherford only knew the gold nucleus (or the sum of the gold and alpha radii) was smaller than 27 fm (2.7×10−14 m)

Other applications

The principle of scattering is now routinely used in Rutherford backscattering spectroscopy (RBS) to detect heavy elements in a lower atomic number matrix, like for example heavy metal impurities in semiconductors. In fact, the technique was also the first local analytical technique applied on the moon, as an alpha-scattering surface analysis instrument was operating just before the Surveyor 4 mission impacted the lunar surface. The same type of instrument was landed on the lunar surface for more leisurely period of data acquisition on Surveyors 5 through 7.

Extension to situations with relativistic particles and target recoil

The extension of Rutherford-type scattering to energy regions in which the incoming particle has spin and magnetic moment, and is traveling at relativistic energies, and there is enough momentum-transfer that the struck particle recoils with some of the incoming particle's energy (so the process is inelastic rather than elastic), is called Mott scattering.[2]

References

- ^ E. Rutherford , "The Scattering of α and β Particles by Matter and the Structure of the Atom",Philos. Mag., vol 6, pp.21, 1911

- ^ Hyperphysics link

Textbooks

- Goldstein, Herbert; Poole, Charles; Safko, John (2002). Classical Mechanics (third ed.). Adison Wesley. ISBN 0201657023.

External links

- E. Rutherford, The Scattering of α and β Particles by Matter and the Structure of the Atom, Philosophical Magazine. Series 6, vol. 21. May 1911

- Geiger H. & Marsden E. (1909). "On a Diffuse Reflection of the α-Particles". Proceedings of the Royal Society, Series A 82: 495-500. doi:10.1098/rspa.1909.0054.